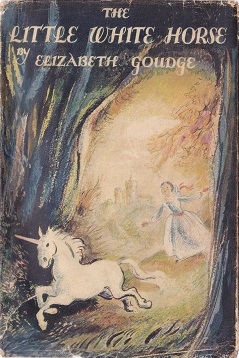

I was excited to get to the 1946 winner, Elizabeth Gouge’s The Little White Horse. I remember watching the TV adaptation, Moonacre, as a child, but I had never read the book and at the time didn’t even realise that there was a book. I don’t remember anything about the TV adaptation either, except the sense of something magical and exciting. The book certainly is magical and exciting, but what I enjoyed about it even more is its wry humour. The introduction of the protagonist (Maria), her governess Miss Heliotrope, and her dog Wiggins is a delight: contemplating her beautiful boots gives clothes-conscious Maria ‘a moral strength that can scarcely be overestimated’, virtuous Miss Heliotrope is afflicted by indigestion that has the unfortunate side effect of giving her the purple nose of an alcoholic, and as for Wiggins…

[I]t is difficult to draw up a list of Wiggin’s virtues… In fact impossible because he hadn’t any… Wiggins was greedy, conceited, bad-tempered, selfish, and lazy. It was the belief of Maria and Miss Heliotrope that he loved them devotedly because he always kept close at their heels, wagged his tail politely when spoken to, and even kissed them upon occasion. But all this Wiggins did not from affection but because he thought it good policy.

There’s a real savour to these descriptions that I love, and it carries on through the rest of the book. This, I think, is what makes this book really successful; it is also deeply concerned with questions of virtue and in the wrong hands this story could have become sickly, but the humour lifts it out of danger.

The Little White Horse returns to some of the themes we have seen in previous Carnegie winners, notably the emphasis on the pastoral and the interest in heritage. At the start of the book, recently orphaned Maria is travelling to live with her uncle in the West Country, a prospect she regards with dismay. Predictably, none of the discomforts she associates with country life materialise: in fact, she is stepping into a picture postcard world in which:

The cottages all looked prosperous and well cared for, and besides the gardens the gardens had beehives in them. And the people looked as happy and prosperous as their homes. The children were sturdy as little ponies, healthy and happy, their mothers and fathers strong-looking and serene, the old people as rosy-cheeked and smiling as the children.

Although she is ‘a London lady born and bred’ Maria fits perfectly into this rural world, so much so that she finds she has a bedroom with a door so small only she can enter, where she daily discovers clothes and other goodies which fit perfectly. Furthermore, she has a destiny to fulfil: she is the ‘Moon Princess’ who has the chance to right the wrongs and heal the old rifts which have marred the happiness of her ancestors. Just in case there should be any doubt about the symbolism attached to her healing of the land, she is assisted in her quest by a lion and a unicorn.

This is, then, a book which is concerned with national identity, and with a vision of Englishness (and I think in this case we are dealing with Englishness rather than Britishness) which is rooted in a particular rural idyll. The world that Maria is seeking to preserve is also distinctly old fashioned – the book is set ‘in the year of our grace 1842’ and Maria is invested in ensuring that Silverydew ‘should never change’. By the end of the book, everyone is happily and heteronormatively paired off, religion rather than personal gain is in the ascendancy, and there’s a sense of happy stasis. This seems in contrast to some of the earlier books I’ve looked at where there was a strong sense of futurity.

At the same time, the book isn’t necessarily conservative. I was interested in the legacy of conflict Maria needs to deal with, which reaches back to the ‘Men from the Dark Woods’ (French – so certainly reproducing some age old British xenophobia) and her ancestor who may have tricked them, and has echoes in the generation immediately before hers. Although the ‘Men from the Dark Woods’ are clearly presented as a dark force, it’s also clear that Maria’s own ancestors have behaved badly and that children inherit the failings of their parents. Reading it as a metaphor for national identity suggests that the rural idyll isn’t an entirely innocent one and acknowledges the possibility of negative histories as well as positive ones. Although I’ve said that this book is not very future focused, it is concerned with resolving and atoning for past crimes in order to move forward. These are concerns that will recur (in a much more hard-hitting way) in a later Carnegie winner, Alan Garner’s The Owl Service.

This isn’t a book for everyone, although it’s very much a book for someone like me – everything from the fantasy elements, to the humour, to the recurrent descriptions of delicious food are calculated to please me. (They also pleased J.K. Rowling, who cites this as one of her favourites.) It’s slower and more descriptive than a typical children’s book today, which might deter some contemporary readers, but I think it does hold up for the right kind of reader. I’m certainly happy it is still in print.

SOME UNSCIENTIFIC RATINGS AND NOTES…

My overall rating: 8/10 – I really enjoyed this, and I suspect if I’d read it as a child my rating would have been even higher – all the fantasy elements would have seemed even more magical.

Plot: 8/10 – This is plottier than a lot of the other books I’ve read so far, and the plot is handled well, although I found the pairing off of everyone at the end a bit uncomfortable (Maria doesn’t actually get married, but I wish her eventual marriage hadn’t been quite so settled as it was)

Characterisation: 9/10 – As is probably already apparent, I love the characterisation in this. I particularly loved the fact that all the characters are quite flawed and that we’re supposed to recognise that. She does lose hold of her focus on character as the plot gets going, though.

Themes: Magic, countryside, nationhood, morality, evil

Publisher: University of London Press

Illustrator:C Walter Hodges (but mostly absent from my edition, alas)

Author’s nationality/race: White English